Turning a static website more dynamic

This blog posted started out as a presentation I gave at the GitHub Nova 2020 conference. The slidedeck is available here.

Since its creation in 2015 the OctoPrint plugin repository has been realized as a static website, powered by Jekyll and hosted on GitHub Pages. Every single registered plugin is an entry in a plugin collection and consists of a chunk of metadata (encoded in YAML frontmatter) and a lengthy description in Markdown as the actual content of the the plugin’s detail page on the repository.

The problem with this static page approach since the begin has been that the information that can be presented inside the plugin repository is static too. There’s no backend for the repository that could keep track of things like popularity of plugins, additional data like source code updates or just a simple “like” feature. And with the ongoing migration away from Python 2 and to Python 3 there comes an additional problem, that of outdated metadata on the plugins themselves regarding Python compatibility, since a lot of maintainers forget to update their registration entry when they add Python 3 support to their plugin.

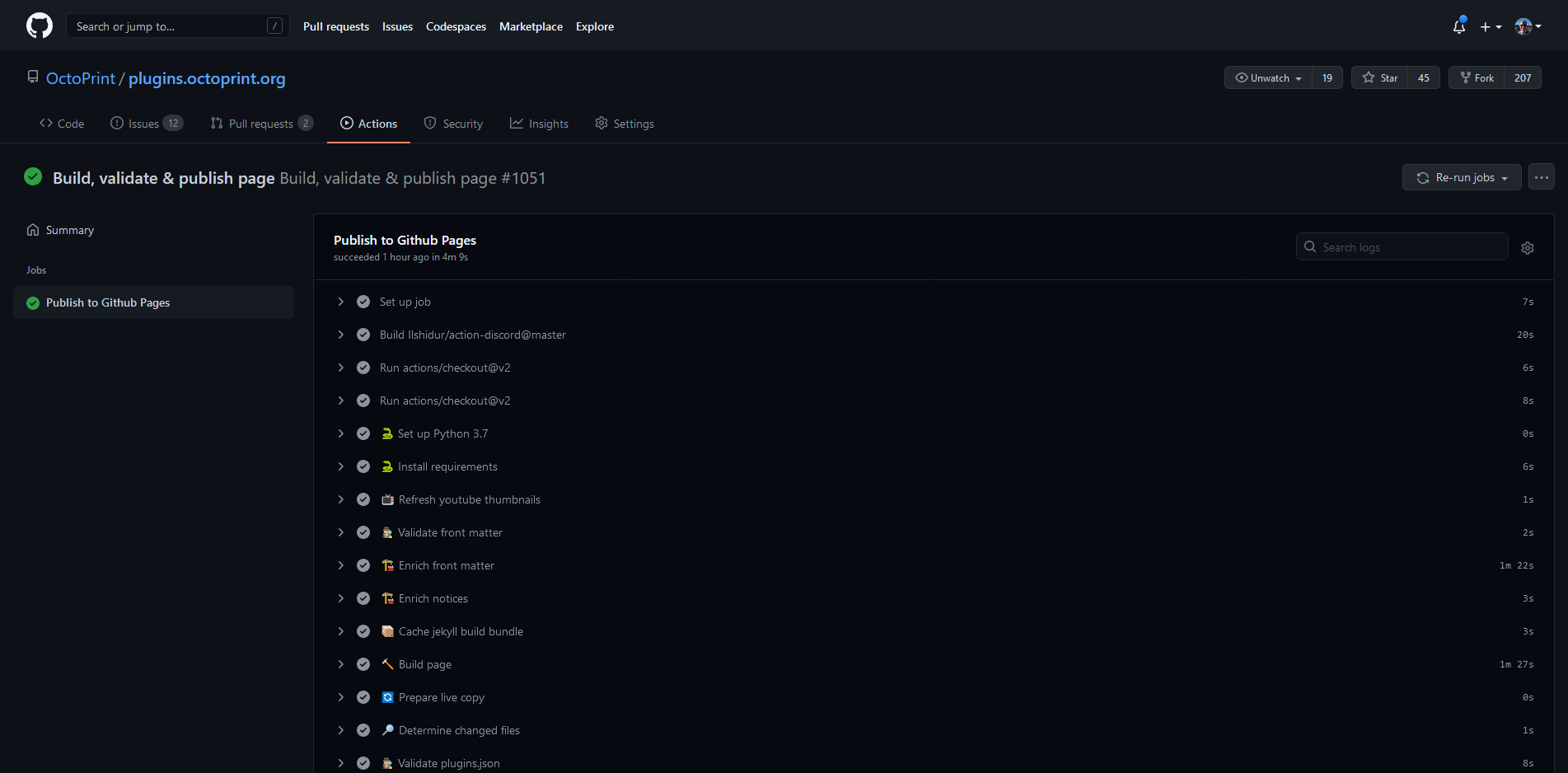

What the repository desperately needed was becoming a bit more dynamic, and with the public availability of GitHub Actions and thus the possibility to build the whole page more frequently and also customize the build workflow that became possible!

Switching the build over to an Action workflow was fairly trivial, once some caching was ironed out (pulling in all Jekyll dependencies for every single page build blew up the build times 😅). With a custom build workflow now in place, responsible of building the static page and triggered on a schedule at least twice per day or whenever there are changes to the static data, it was possible to add additional build steps.

Adding usage data

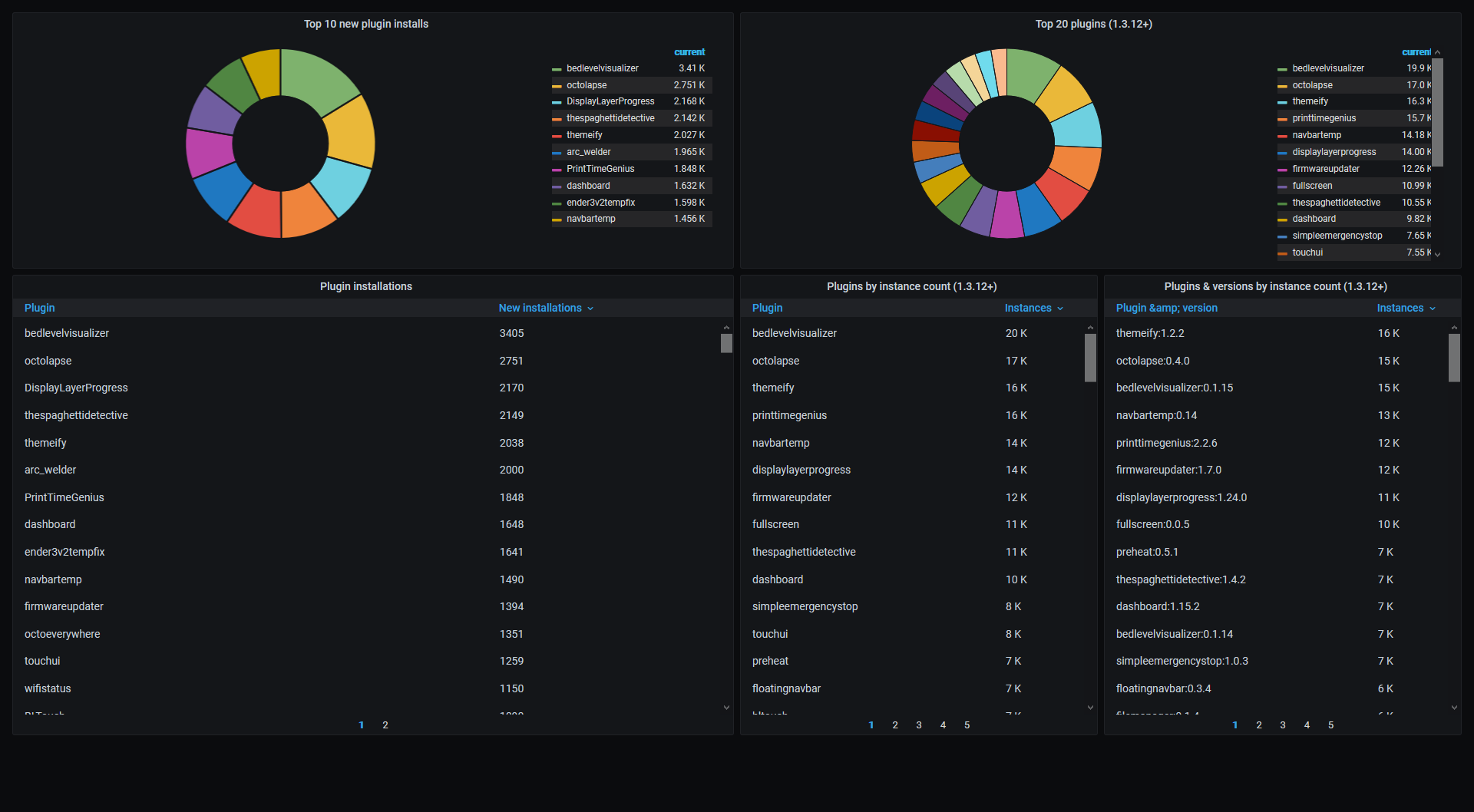

The first step was to add data enrichment of the plugin metadata in the frontmatter using the plugin usage information collected by the Anonymous Usage Tracking on tracking.octoprint.org.

As a bit of background on this opt-in tracking setup, it is completely self-hosted and

consists of an nginx web server with a very custom log format.

The Anonymous Usage Tracking plugin - if enabled - sends well-defined requests to an

instance specific endpoint on this nginx server. That request

gets logged to the access.log. Logstash is then used to parse this log data, extract

the event data and pump it into an ElasticSearch instance. From there it can be visualized

using a private Grafana dashboard, which you might have seen already in some episodes

of OctoPrint On Air and also in screenshot form on the OctoPrint twitter account.

Since OctoPrint 1.3.12 the tracking plugin also sends a list of all installed plugins and their versions to the tracking server, and that data is what I was after for this usage data enrichment step. With the number of installations out there in the wild, it would be easy to create a list of popular plugins. Based on the number of new installations per week, it would be possible to get a sense of which plugins are currently popular or “hot”.

But how to get the data from ElasticSearch into the frontmatter of the plugin repository’s plugin data files? The solution to that consists of an export run each hour on the tracking server, querying the relevant data from the ElasticSearch instance and dumping it into an easily parsed JSON format available on data.octoprint.org/export/, then - using a custom build step - pulling that export in during page build, extracting the data for each registered plugin and enriching its frontmatter accordingly.

Me being a Python person I obviously opted for an enrichment step in form of a Python script,

utilising requests for fetching the current

export(s) and using the frontmatter package

to enrich the metadata. Now all the plugins had usage data as part of their

frontmatter, and using Jekyll’s sorting and filtering methods it was now easily possible

to build Top10 lists!

GitHub metadata and parsing ASTs

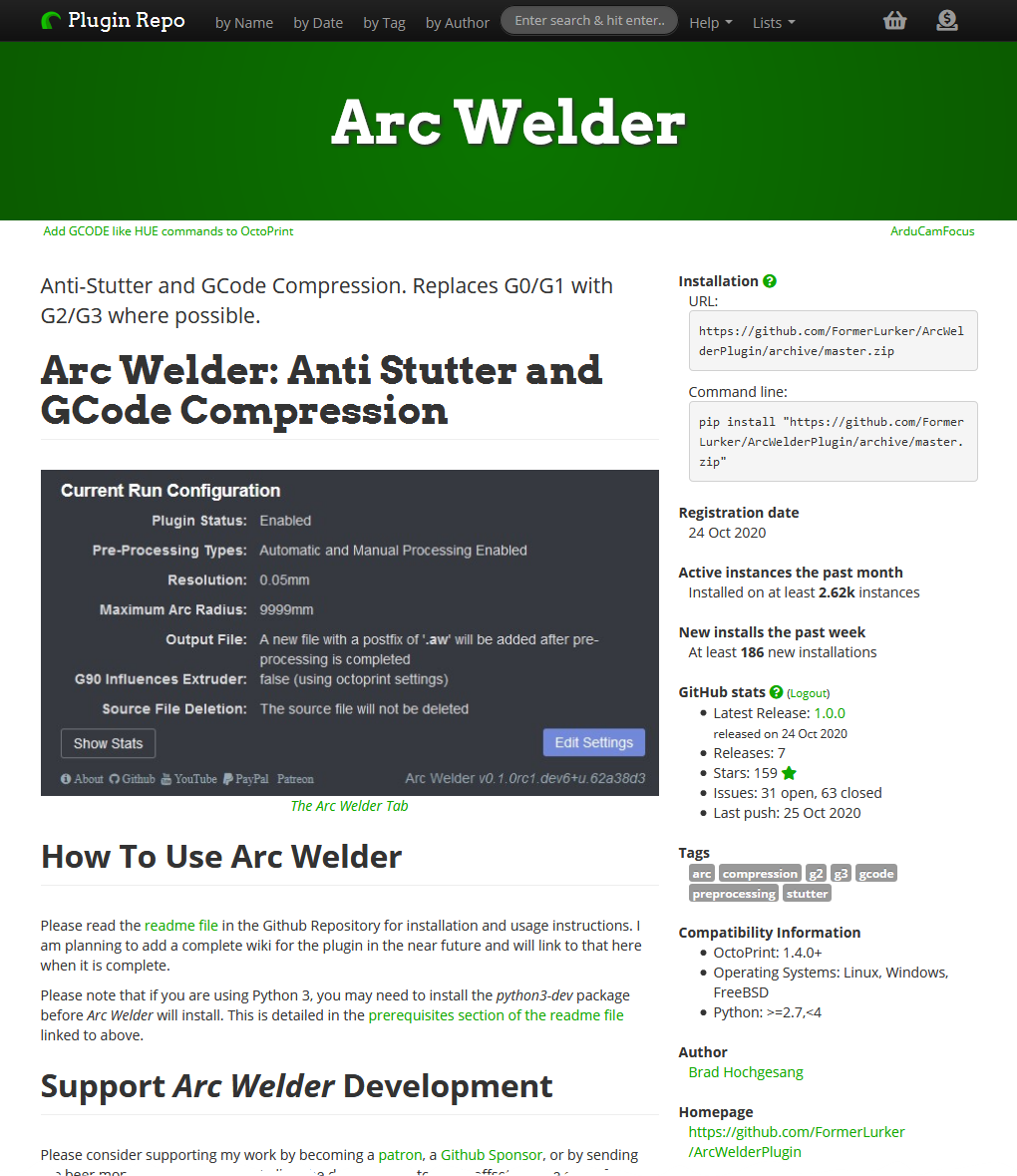

So now we had information about the popularity and usage attached to the plugins. But there still was no information at all about whether a plugin was also actively maintained by its maintainer(s), when the last release happened and there was also still no guarantee of the compatibility data being correct.

Enter the next step. Most plugins currently registered on the OctoPrint Plugin Repository are hosted on GitHub themselves. GitHub has a bunch of nice APIs to query all kinds of metadata of its repositories, so the next step was to further enhance the enrichment script to also identify those plugins hosted on GitHub (easily done by inspecting the source code URL) and fetch activity information from GitHub’s APIs.

To work around some request rate limits here and also to make everything faster, @OllisGit had the great idea to use the GraphQL API for this query step, instead of running multiple requests per plugin against the REST API. By further parallelizing the I/O heavy process, the build times could be kept low.

Ensuring the accuracy of the compatibility information involved another substep for the enrichment script that consisted of fetching the main plugin file from its GitHub repository and extracting the compatibility flag used by OctoPrint itself directly from it, without trying to execute it. Using the same AST parser based approach as used in OctoPrint this was surprisingly quick to pull off as well and once run quickly made the Python 3 compatibility rate on the whole repository jump up by around 15%. So another pain point taken care of.

Stargazing

The final thing I wanted to achieve was a way for plugin users to also show some appreciation for plugins they like, giving the authors some additional feedback. At least for the plugins hosted on GitHub, there’s a mechanism like this already available as you can star repositories you like/find interesting/want to give a thumbs-up. But how to integrate that with the plugin repository?

The answer to that was using the information about whether a plugin is hosted on GitHub, and if so in which repository, extracted by the enrichment script to utilize the starring API. For that, I needed a way to allow the user to authenticate with GitHub so that I could fire off authenticated requests in their name to star/unstar a plugin.

The GitHub star proxy was born. Written in Python using flask and flask-dance and quickly deployed in a docker container, that little thing allows you to get authenticated with GitHub and then star repositories hosted on GitHub, right from the plugin repository’s client side through some JavaScript code.

Final pain point taken care of.

Results

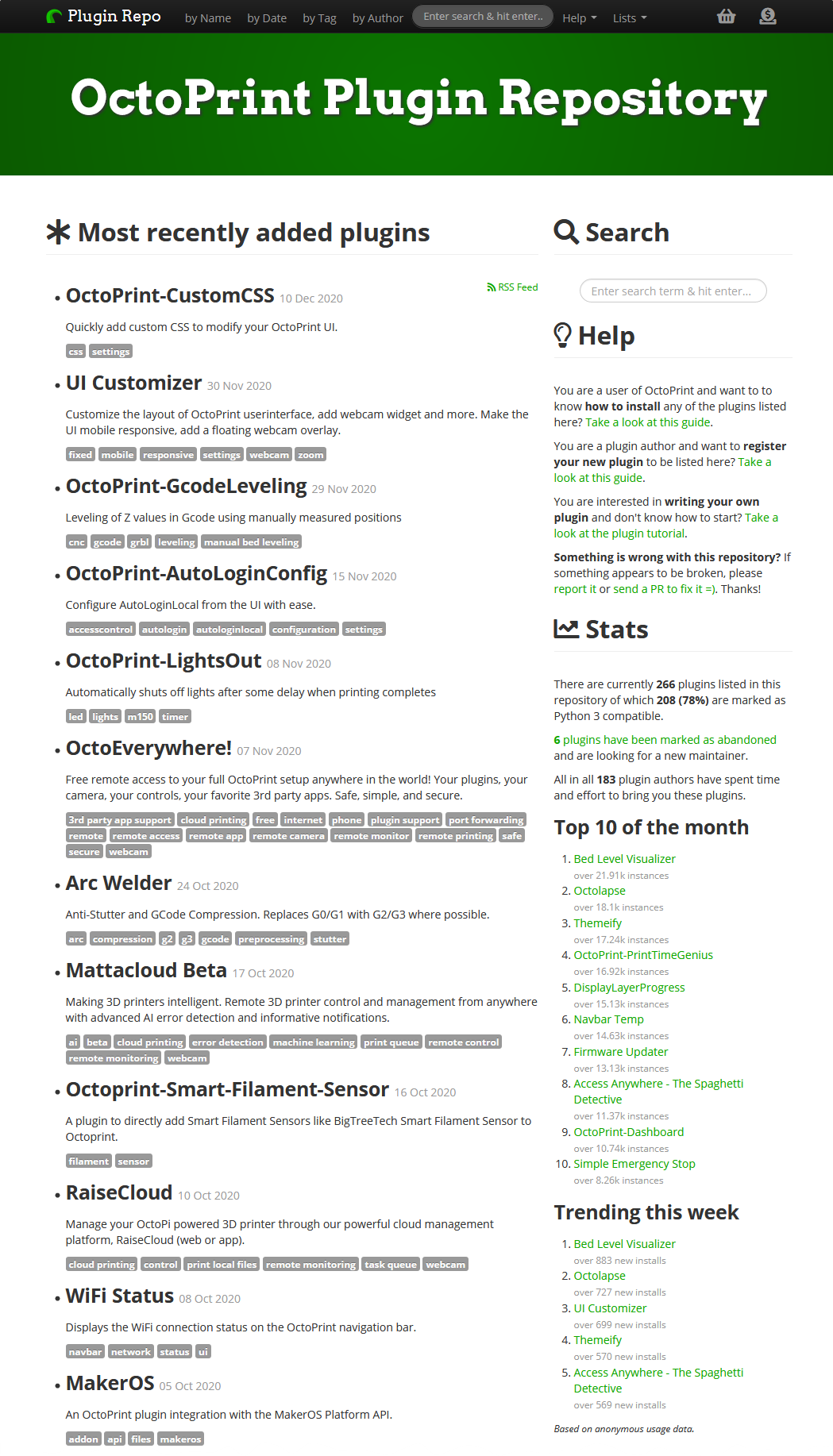

With all this coming together, we are now at a point where each plugin’s details page has current usage data and - if hosted on GitHub - also some “project health” metrics like latest release, star count, opened and closed issues and when the last push happened to the main branch. The compatibility information is more reliable now as well. And - if so desired - users can now also log in and star plugins right from within the repository.

The repository now also features some nice rankings, showcasing popular and currently trending plugins prominently right on the start page.

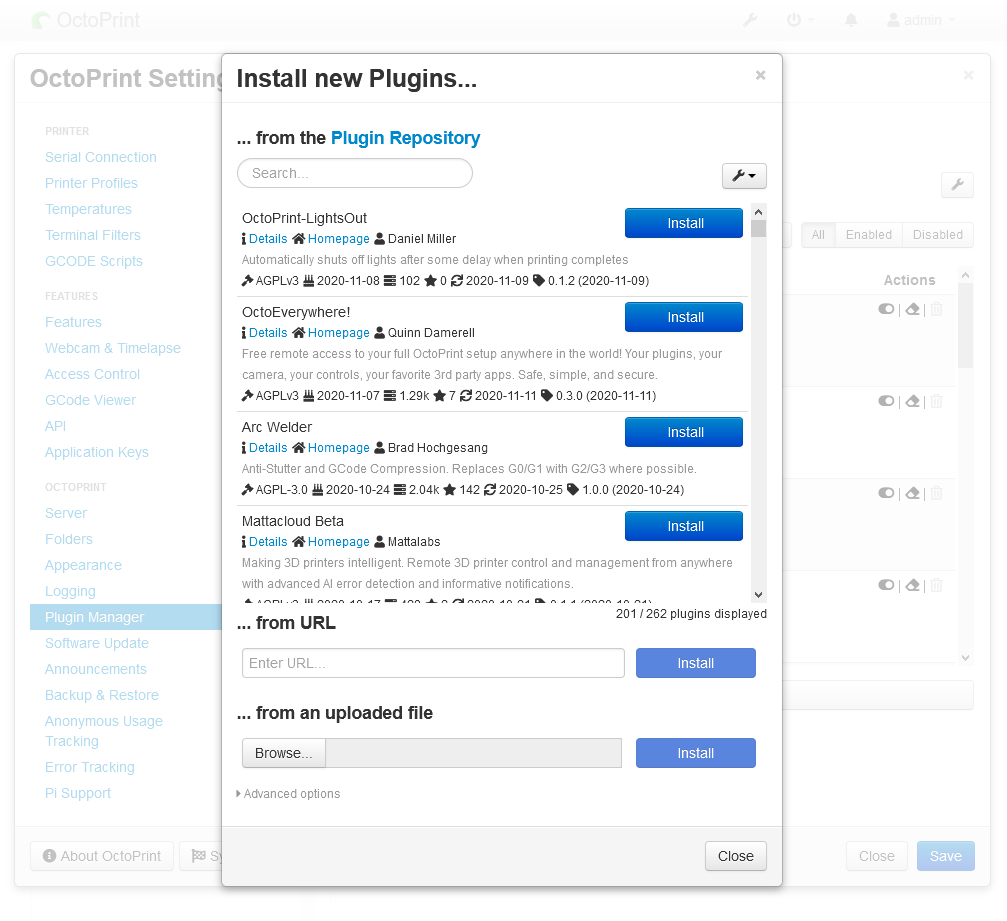

And all of this new data of course has found its way back into OctoPrint’s built-in repository browser as well, where you now can also sort by popularity, latest release and similar. The only thing not yet available there (for now 😉) is starring.

This being an Open Source Project, the sources for all of this are obviously available. If you want to take a look at build workflow, enrichment & validation scripts or the page source of the repository itself, take a look at github.com/OctoPrint/plugins.octoprint.org. For the starring proxy checkout github.com/OctoPrint/github-star-proxy. Finally, for the usage data exports you might want to take a look at data.octoprint.org/export/.

And since this is the final blog post of this crazy year of 2020, let me take the opportunity to wish you all Happy Holidays 🎄 and a Happy New Year 🥂! Stay safe!

- Published

- 15 Dec 2020

- Category

- Development

OctoPrint.org

OctoPrint.org

Discuss!